Pills

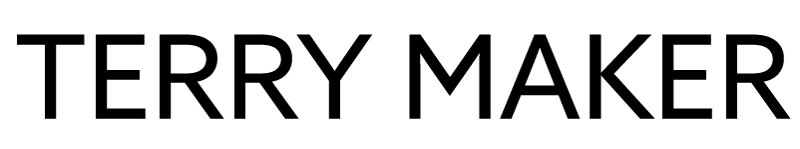

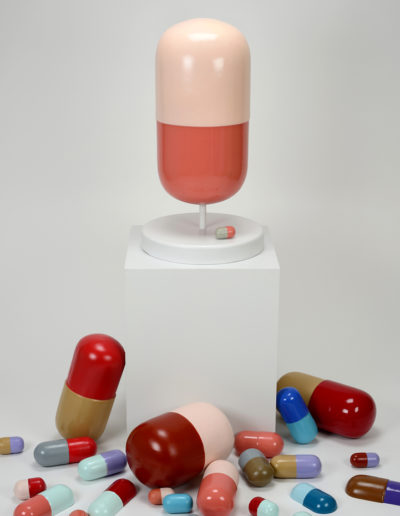

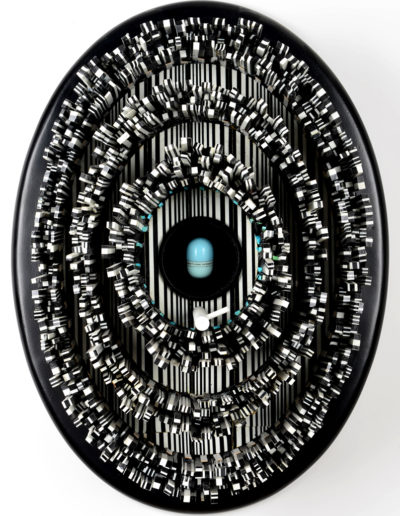

The Pills series is a contemplation of the nature of remedies for sickness. If the piece The Great Physician offers an entry point into the series as a whole, then the combination of a giant pill capsule and a comedically literal Jesus-hand hints that the material is the spiritual—that sickness has a metaphysical component connected to the physical. If the entry point is instead the gaily Seussical Root of Jesse, which references the biblical “branch” that offers healing for the nations, then the spiritual component of healing is understood to be communal, rather than individual, in nature.

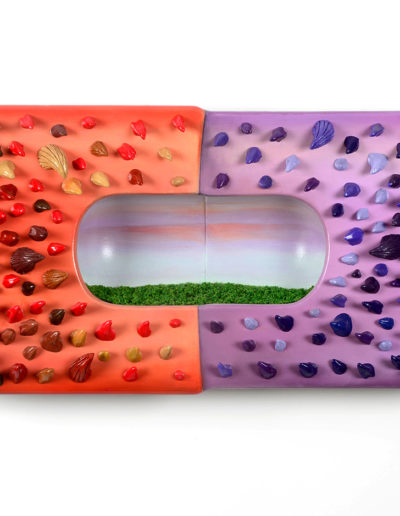

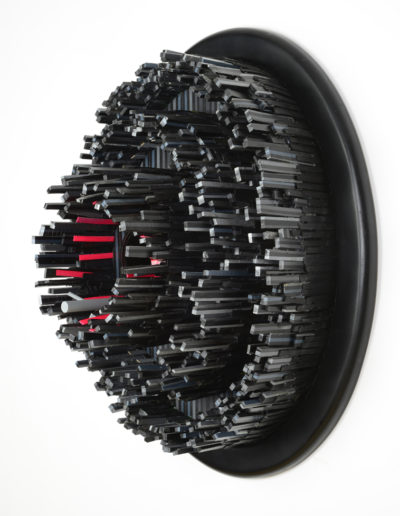

The various depictions present pills that are, if rather large or excessive in number, at least somewhat attractive to the eye. Bitter Pill and the thorn-studded Balm of Gilead, although also aesthetically attractive, are pointed reminders that while medicine may be beneficial, it is not always pleasant to take. The latter work hints that sometimes the bitter unpleasantness can be borne by another for the sake of the vulnerable; although that piece was created prior to Covid-19, it’s an insight whose meaning has been revitalized by the social dynamics of the pandemic.

There is no one in history more familiar with the proverbial bitter pill than the “blameless and upright” patriarch Job. One can see in the piece Job’s Lament the depiction of his uphill battle of trying to hold on to faith in the midst of the silence of the heavens, even as Job’s situation just kept getting worse and worse. While his suffering led him to wonder if he would have been better off never being born, Shakespeare’s Hamlet pondered the other end of life, when we face our final, permanent sleep, Perchance to Dream. Shakespeare recognized that the bitter pills of life often leave us tempted to leave it behind altogether. But such thoughts, the fruit of suffering, lead us naturally to consider what we face after “we have shuffled off this mortal coil.”

We seldom think such thoughts, or ask the big questions, in the absence of pain. Perhaps suffering, then, while physically and psychically dreadful, can sometimes be existential medicine.